In recent decades, corrections has shifted its focus to place an increased emphasis on rehabilitation and reentry. With this renewed focus, recidivism rates have seen a decrease of approximately 43 percent among formerly incarcerated individuals who pursued education or vocational training prior to release, according to a study conducted by the Rand Corporation.

As CoreCivic celebrates its 40th anniversary, a longtime corrections professional and company leader, Matt Moore, reflects on this industry shift. Moore, who serves as senior director of Reentry Services at CoreCivic, has been in the corrections field for 35 years and has watched the pendulum swing. He says the public has realized over time that incarceration alone doesn’t prevent people from returning to prison.

“It’s ineffective to just incarcerate individuals for public safety alone,” he said. “We must do something more to ensure they are fully rehabilitated once they leave prison.”

While education is often a central pillar for reducing recidivism, it’s not the only remedy. Often, a combination of methods is needed to address each inmate’s primary motive for committing crimes.

“When we address these issues, factors and deficits, we have a really good chance of making a difference,” Moore said.

In many cases, the way a person thinks can predict how likely he or she is to commit a crime. Other factors are their friends—the people they hang out with most—and the quality of their coping skills; their family dynamics; their employment status; their education level; and how they choose to spend their leisure time.

“There’s usually one issue that’s driving all the rest,” Moore explained.

At CoreCivic facilities, inmates are screened in a variety of ways to determine what has driven their past behavior and how to properly address it. They’re not only assessed at the beginning of a program, but also at the end, to see how their thinking has evolved.

Cognitive screening techniques measure a person’s sense of entitlement and look at how they may justify or rationalize their actions. How much empathy do they have? Are they more interested in maintaining a sense of power and control, rather than acknowledging how their actions might affect others?

Ultimately, behaving in a socially acceptable way is a choice, but for many inmates, it comes down to the way their thinking is “wired,” according to Moore.

“Some of our program offerings help facilitate cognitive restructuring that leads them to think differently, and move away from criminal patterns,” he said.

With more productive thinking, inmates may realize the best way to improve their lives when they leave prison is to find steady employment rather than participate in criminal behavior. But before they can do that, many must build up the requisite skillset that will enable them to find positive pathways instead of reoffending.

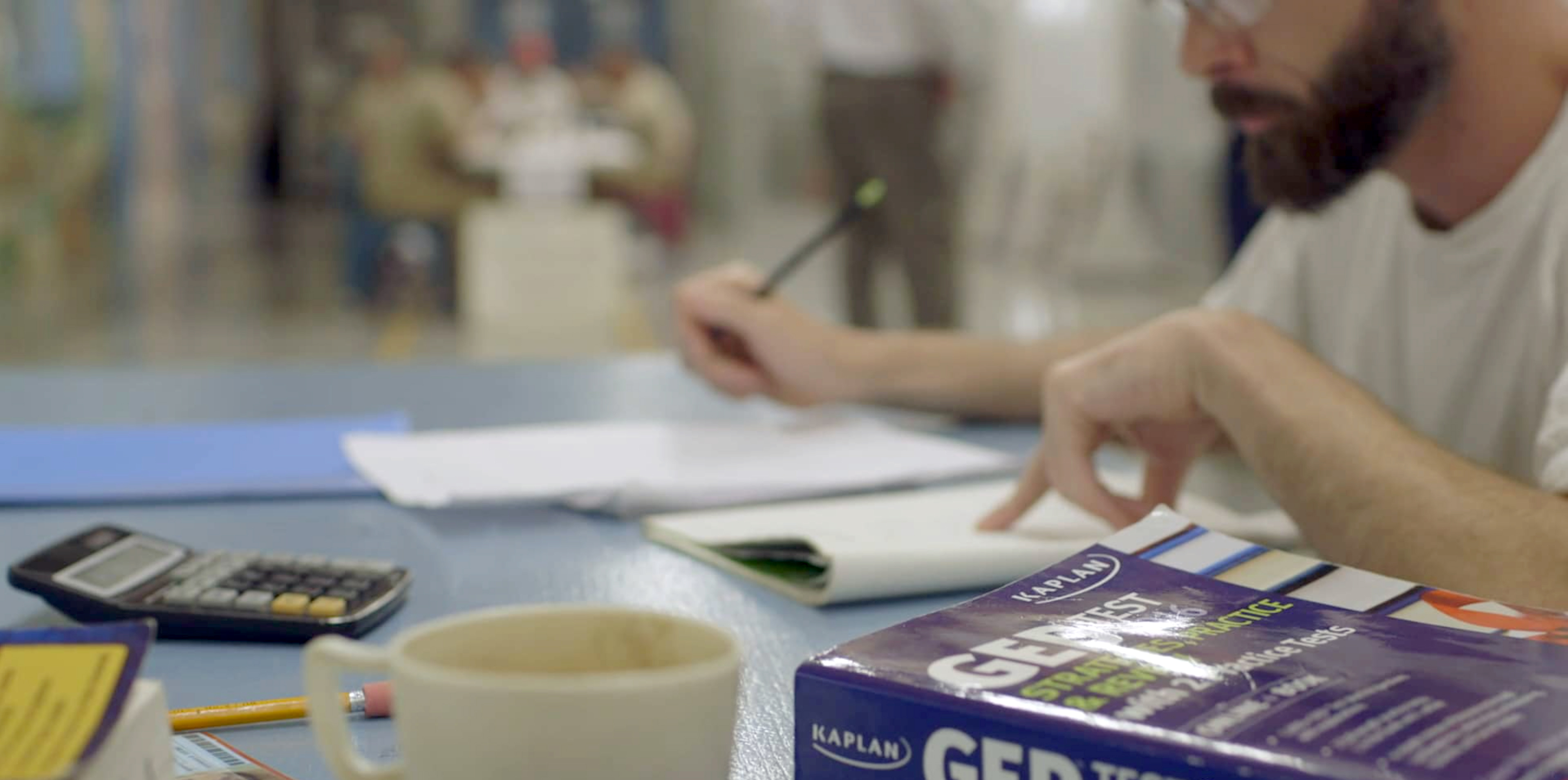

That’s why CoreCivic has built a robust suite of educational and vocational training as part of its reentry programming.

“We’ve got some really strong, values-driven leadership that sees the importance of this kind of programming and knows it’s the right kind of care to offer to incarcerated individuals,” Moore said.